Is AI a Bubble? Why History Says We’re Not There Yet

- Isha Simha

- Nov 26, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 26, 2025

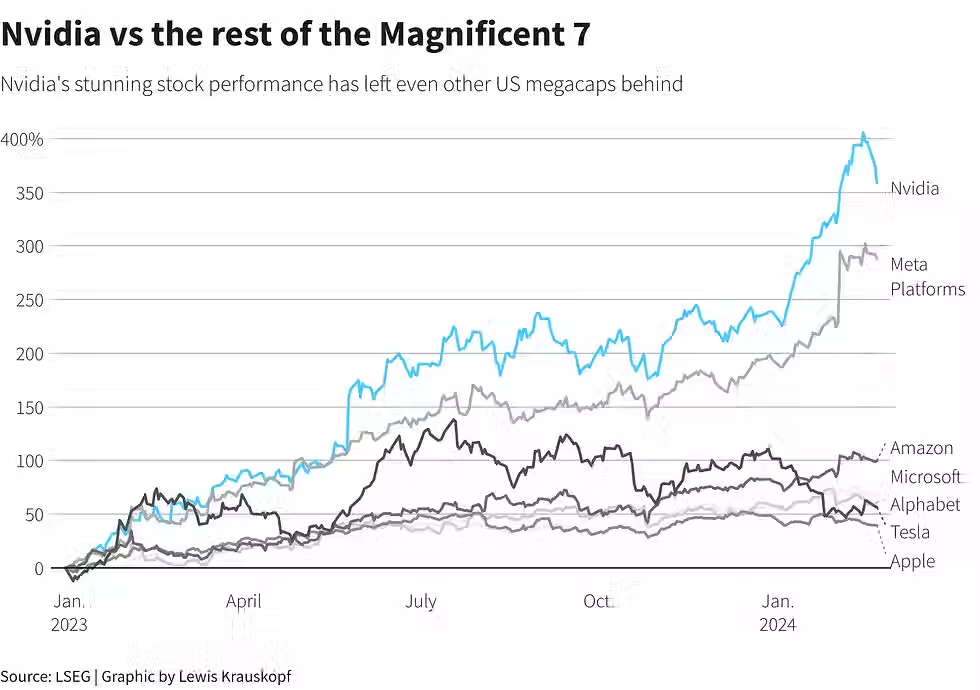

Something has shifted in the last eighteen months. The pace of AI headlines, fundraises, and market reactions has stopped feeling like innovation and started feeling like acceleration as too much capital chases too few certainties. Whenever Nvidia reports earnings now, Wall Street pauses as if waiting for a new weather pattern to roll in.

People are asking the obvious question: Is AI actually in a bubble? It’s a fair question, especially when one of the most famous bubble-spotters alive, Michael Burry, is loudly betting that it is.

But clarity requires stepping back from the noise. Hype cycles always feel confusing from the inside. The trick is to find a model that describes where we really are, not where the loudest voices insist we must be.

This is my attempt to map the moment: a cycle defined by infrastructure, capital flows, historical echoes, and a very human psychological momentum.

A Shock to the System

Let’s start from the ground truth. The AI boom is not just a software story. It is a physical build-out on a scale modern tech hasn’t seen since the cloud displaced on-premise computing. We are witnessing a global scramble to secure three scarce assets: GPUs, Power, and Land.

Nvidia’s recent quarter was almost unreal with $57 billion in revenue, up 62% year-over-year, the single fastest revenue expansion of any major tech company in history. Jensen Huang’s commentary was equally blunt, “Blackwell is off the charts. Cloud GPUs are sold out. We have entered the virtuous cycle of AI.”

This 'virtuous cycle' is the core of the long-term bull case. More demand creates more compute, which creates more applications and results in even more demand.

To support it, hyperscalers like Meta, Oracle, Microsoft, and Google are raising tens of billions in bond offerings, debt financing what is arguably the largest compute build out in human history.

Most booms are driven by sentiment. This one is driven by capital expenditures measured in gigawatts.

When Capital Becomes Pathological

And yet, capital can move from necessary to excessive in a heartbeat.

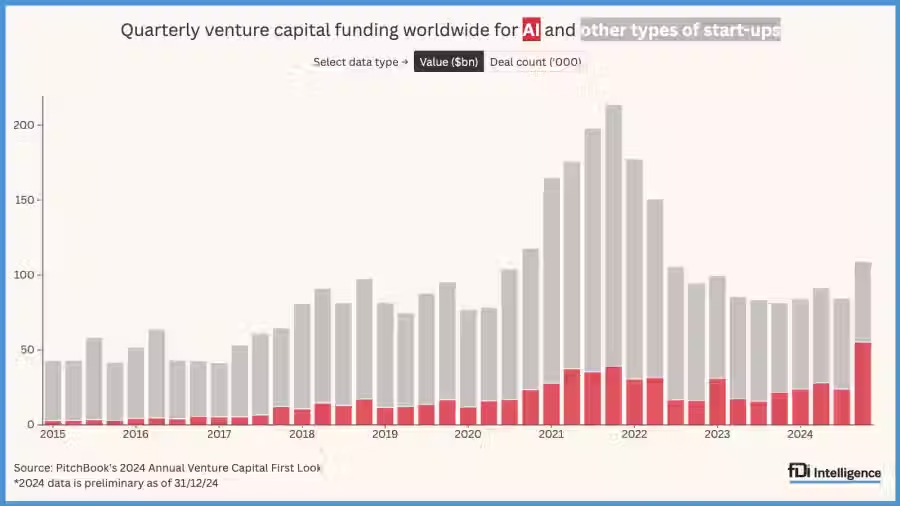

The first visible sign appeared in venture markets. In Q1 2025, AI startups raised $73.1 billion, representing nearly 58% of all global VC. Crunchbase reports that in the first half of this year, almost $90 billion of U.S. venture capital went solely into AI companies.

Founders joke about adding '.ai' to their domains and watching their valuations triple. Investors admit privately, and occasionally publicly, that they are pricing startups based on vibes plus GPU access.

Bryan Yeo of GIC, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, captured it perfectly, "Any startup with an AI label will be valued right up there at huge multiples of whatever revenue it has.”

It’s not new. This kind of behavior is what historians call the exuberance zone, the early stage where rationality starts slipping but hasn’t fully broken.

AI is undeniably in this zone, but exuberance is not the same as a bubble, at least not yet.

Enter Michael Burry: The Ghost of Bubbles Past

No figure commands as much attention in this conversation as Michael Burry. His public declaration that AI is 'dangerously euphoric' hit like cold water in an overheated market.

Burry has:

Deregistered his hedge fund Scion, freeing himself to take unconventional positions.

Posted about history 'rhyming again', comparing Nvidia to Cisco in 1999.

Bought over $1 billion worth of put options against Nvidia and Palantir, the two poster children of the AI rally.

He warns that investors are assuming exponential growth, ignoring profitability questions, and “pouring capital into AI firms on the belief that the technology will rewrite the economy.” To Burry, the parallels to the dot-com era are unmistakable.

And in fairness, he’s not wrong about the psychology.

During the 1999 bubble, retail investors were pouring money into companies like CMGI, a conglomerate of barely operating dot-coms whose stock went from $17 to $163 in a few months before collapsing. Everyone from taxi drivers to college freshmen felt like a day trader; any company with '.com' in the name would double by Friday.

It was mania disguised as technological destiny.

So when Burry asks whether Nvidia, at $5 trillion market cap, is this generation’s Cisco, the company that once became the world’s most valuable tech firm before losing 80% of its value, he is drawing a legitimate historical line.

But here’s where I diverge from him.

History Never Repeats, But It Rhymes in New Ways

Let’s go back farther, to the tulip crisis of the 1630s. The popular story is that tulips became so expensive that a single bulb cost more than a house, and when the market crashed, the Dutch economy collapsed.

The reality is more nuanced. Historians now show only a handful of bulbs ever reached those absurd prices, and the crash affected a tiny elite group, not the whole Dutch economy. Many contracts were never enforced, so losses were limited.

Tulip mania became famous not because it destroyed an economy but because it revealed a pattern: humans are extraordinarily good at convincing themselves that this time, the rules are different.

The same pattern that drove the South Sea Bubble also reappeared in 1929, 2000, and 2008.

But in each case, the bubble required one fatal ingredient, the underlying asset had to be fundamentally worthless at scale. Tulips, South Sea bonds, Webvan (a dot-com era grocery delivery startup that scaled far before demand existed), mortgage-backed securities built on fraudulent loans, none of these assets had the long-term economic foundation people believed they did.

AI is not that.

Nvidia’s earnings alone prove it.

Why Burry Might Still Be Early (Or Wrong)

Even if we take Burry seriously, and we should, there is a structural difference between his 2008 thesis and his 2025 thesis.

In 2008, the entire financial system was pricing garbage as AAA collateral.

In 2025, the market is pricing extraordinary demand for compute that is actually happening.

Burry’s put options were placed before Nvidia reported its most mind-bending earnings in company history.

If Nvidia were a house of cards, we would see:

Slowing data-center demand

Margin compression

Hyperscalers reducing CapEx

Shrinking lead times for chips.

Instead, we see the opposite. Every cloud provider is scrambling to get more Nvidia hardware. Power constraints, not demand, are the bottleneck.

This is why Jensen Huang has repeatedly rejected bubble narratives. His argument is simple, “AI demand is real. It is not speculative. We can’t build infrastructure fast enough.” Even Sam Altman, who openly acknowledges boom-bust volatility, insists that the long arc of AI is unprecedented economic expansion. Cathie Wood goes further, claiming we are “in the first inning” of a multi-decade technological change. Her conviction mirrors that of tech leaders building this ecosystem from the inside.

The Part People Get Wrong: Many of Us Have Never Seen a True Bubble

When younger investors say that AI feels like a bubble, they are usually reacting to retail hype, TikTok AI stock picks, and thin startups raising at impossible valuations.

But true bubbles like 1929, 2000, and 2008 had distinct signatures that many younger investors have never lived through.

In 1999:

Taxi drivers were giving stock advice

IPOs with no revenue were tripling day one

Companies were adding '.com' to their names just to pump their stocks

Valuations disconnected entirely from fundamentals

CMGI and JDSU rose hundreds of dollars per week

Pets.com spent $300B (in today’s dollars) of VC money and generated pennies in revenue.

Compared to 1999, AI hype looks almost disciplined.

Overheated, yes.

Maniacal, no.

The difference is that AI’s core players, Nvidia, Microsoft, Amazon, Oracle, Alphabet, are generating staggering real revenue from real customers. Cisco in 1999 had nowhere near Nvidia’s growth metrics. Webvan in 2000 had no customers. Tulips in 1637 had no utility.

So Is This a Bubble? The Answer Is in the Cycle

When you assemble all the signals, infrastructure, capital flows, earnings, and sentiment, the picture becomes clearer.

AI is in a cycle, not a bubble.

This is the natural shape of technological adoption. AI is not collapsing off the peak, it’s still climbing toward it, fueled by early exuberance layered on top of real infrastructure and real demand.

Cycles have acceleration, fever, pullbacks, consolidations, and then another leg forward. Bubbles have delusion, detachment, and collapse. We are not in collapse territory. We are not even in late-stage detachment.

What we are seeing is early exuberance layered on top of real economic transformation. The money flowing into thin AI startups will absolutely unwind, just like the 2016 ICO bubble unwound, just like the 2012 social app hype cycle unwound. But the infrastructure being built, the GPUs, the data centers, the power grids, the new application layers, will remain.

My View: Overhyped? Yes. Dangerous? Not Yet.

AI is unquestionably overhyped. It is attracting capital indiscriminately, contains pockets of absurdity, and there will be a correction in the next 12 to 24 months as overpriced, no-moat AI startups fail and early VC enthusiasm cools.

But now is not the peak, now is the acceleration. This is not where bubbles pop. This is where they form their shape.

If history is any guide, the real bubble, the destructive one, comes later, when:

Infrastructure is fully built

Consumer applications explode

Productivity gains materialize across sectors

Valuations start pricing in perfection.

We’re still in the build-out phase.

For long-term investors, this is a moment that demands clarity, not fear. Distinguish Nvidia from the 'AI for Dog Groomers' startups. Distinguish foundational models from thin wrappers. Distinguish Jensen Huang’s data center math from retail TikTok hype.

The gold rush is real, but the gold is too.

Comments